Three events prompted this lengthy essay. First, I met Roy Lee on X and then saw him at a founders event in New York City a couple weeks back. His pet project Interview Coder, and now Cluely, inspired a New York Magazine piece about cheating with ChatGPT in college. I’ve noticed more and more of my “elite” peers using ChatGPT. My friends use it and so do my professors.

Second, returning to my home and reaching out to some friends in high school reminded me of what school was like at that age. I came from a well-funded public school located in a New Jersey suburb that wasn’t particularly diverse. Less than ten Black kids, maybe a Hundred Hispanics, but predominantly White and Asian. Fewer than 30 students on free or reduced-price lunch as well.

Third, transfer admissions results started coming out. I had already received a number of people asking me for advice on their application, and now I have nearly a dozen people in my DMs across X, LinkedIn, and Instagram asking me about Duke. In addition, a friend from high school sent me a Substack post that screenshotted my thread about a Reddit kid’s crashout upon getting rejected from several top universities. Nothing like more of your fifteen minutes to get you motivated to write again.

Education is under attack. At every level from pre-K to graduate school, the academy is barely managing. Harvard is engaged in a torrential lawsuit against the Trump administration. Generative AI is questioning the value of the written word, and New York Magazine certainly wasn’t the first to point that out. Elite college students are struggling to read, as this article and one of my old TikToks about the article mopes over.

Disability accommodations, fueled by pill mills, add in another dimension to mental health and education. Personally, I know a non-zero number of people who have abused accommodations to get extra time and study drugs for everything from the SAT to their college finals. The difficulty of elite college admissions still makes headlines, both online and for the average student. There’s no shortage of blog posts, Reddit posts, and opinion pieces from fancy newspapers deriding both how exclusive and inclusive top universities have become. Public schools have faced budget limitations for decades, and Trump’s Education Department isn’t going to make that any better. School vouchers and more private schools only fuel an inequity in baseline education. Despite that, it’s also been long known that throwing more money at schools doesn’t lead to performance improvements. Not only are kids incredulously vaping in the handicap stall, but they’re also breaking their Chromebooks?

Something is seriously wrong with this whole picture, and it doesn’t take a 1600 SAT score to realize that. Education has increasingly become stratified. At the same time of all this depressing news is other news of young geniuses winning international academic competitions or dropping out to join Palantir’s anti-academia initiative. The achievement gap between the elite and the not elite has become an abyss, expanded by copious amounts of privilege and wealth.

I’m going to do my best to address this set of challenges in three parts to answer three different questions. First, how should education address disruptive technologies? Second, how should higher education and its admissions be understood and reformed? And last but not least, how should we raise the standard of education for the people that need it the most?

Artificially Intelligent

About a month ago, Secretary of Education Linda McMahon and former WWE executive left a panel baffled when she started talking about A.1. sauce. She said, “there was a school system that’s going to start making sure that first graders, or even pre-Ks, have A.1. teaching every year”. While teachers aren’t going to be replaced by a condiment any time soon, the very person supposed to lead education in America talking about a sauce is pretty terrible to hear given what’s at stake.

Generative AI has the potential to be widely influential. It may democratize access to specialized instruction and give each student or parent the ability to customize curriculums. When used correctly to provide feedback or explain things step-by-step, it works well to fill the gaps that a teacher or professor might leave out.

The problem, and sad truth, is that very few students are actually using AI in this capacity. Students at every level from grade school to Ivy League universities are using tools like ChatGPT to cheat. They screenshot physics problems or copy-paste in entire treatises to see what ChatGPT has to say, not what they have to write. Consumer AI is so capable at this point that you can use it to transcribe lectures in real time, send it to ChatGPT for a summary, and then plug that summary into writing an essay for later. STEM students are feeding in their labs or projects and asking ChatGPT to do it for them. Debugging a complicated web of code is already assisted by AI at big tech companies, so why not do the same for your data structures and algorithms final project?

Cheating is not new, but in the same way that AI could have democratized education, it’s only democratized cheating. It is now laughably easy to cheat your way through a college degree. With providers like OpenAI and Google making pro versions of their large language models free for students ending after finals week for quarter system schools, it’s almost like they know the exact use-case. In fact, they definitely know.

I have two pitches for this: one to students and one for how teachers, professors, and administrations should respond.

For students, I simply ask why? What is the point of going to school if you’re going to cheat through it all? Why pay up to $100,000 a year at some fancy private school if learning how to prompt ChatGPT is all you will learn? College degrees used to signal status and competency, the more exclusive the institution, the better. But now? You’re eroding the value of your mind and your degree when you use AI to complete assignments. If you think that education and knowledge has some intrinsic value, AI erases that. Even if you’re compelled by a prestigious job that your fancy degree will get you, will AI actually make you better at that job compared to your elders who had to get through it without AI? Will you understand something from first-principles if you just use ChatGPT to finish your labs? You might not be destined to be a writer and think that writing is beneath you. Still, writing is itself a cognitive exercise and you should want the ability to write (and thus think) clearly. If you’re in a reading and writing heavy discipline like English, philosophy, or political science, what use is the slop summarized or generated by AI? Do you think you get the full picture? The nuances of information-dense text?

You’re in school to train your mind. Shortcuts are easy, comprehension is difficult. I won’t even try to grandstand, mainly because cheaters are often successful, but I will try to appeal to your sense of curiosity. If you are at all curious about learning, falling back to generative AI is the greatest hindrance to your education. You can write better than AI. Your lifetime experience and emotions are things that next-token generators will never have. AI is dangerous to use, an infohazard of some sort. You may have already irrevocably curtailed your ability to problem solve, pay attention, be creative, or even remember things. Stop before it’s too late.

For everyone else, I think it’s pretty clear what needs to happen if you want to create an environment where students actually have to learn information. It’s back to in-person exams. Ditch the laptops and return to how it was done before. Students at every stage have broken the trust of doing exams remotely. Why trust them to reverse track? Education needs an overhaul, one without AI at every corner despite what EdTech companies want for their bottom line. Take actual measures to gauge the competency of students. Have them write papers in-person, make labs or projects impossible to ChatGPT, or even give interview-style exams. Anything to prevent AI from creeping into their performance. Bolded prohibitions and warnings in syllabi that no one ever reads is not enough. If you want to stop the use of AI in the classroom, you need to make it impossible to use in the first place.

For the purposes of education, AI is a desecration to everything that learning stands for. It isn’t fair to a classroom where individual performance matters. It isn’t fair to you, as someone who must wade through generated slop. It isn’t fair to the practice of education.

Admissions, Prestige, and the Average College Student

Whenever I talk about the subject of elite colleges, I think it’s always good to put it into perspective. There are roughly 3.7 million high school graduates in the United States per year. The sum total of Ivy-Plus (per Raj Chetty’s definition: the eight Ivy Leagues, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and UChicago) first-years is 22,814 students. In other words, 0.61% of graduates attend an institution of this level, not to count the fact that these universities also enroll a high proportion of international students. With that, probably closer to 0.5%.

That’s it. Half a percent of high school graduates in America attend this group of universities. All the posts, all the discourse, all of everything applies to a very narrow sliver of the population. And yet, if you’re reading this, your feed is probably dominated by students and alumni of these institutions. American society, and perhaps Americana influence abroad, has elevated a select number of institutions to star status. Like it or not, we think highly of these students regardless of their actual academic, intellectual, or practical capabilities. We fight, get emotional, and chase the status of a few schools. For what? Because we think it’ll get us a job in finance, consulting, or big tech? Something along those lines.

I, admittedly, have read a sordid number of books on elite universities and admissions. I’d give a quick shoutout to the following if you’d like to learn more:

Andrew Delbanco’s “College: What it Was, Is, and Should Be”

Jeffrey Selingo’s “Who Gets In and Why”

Paul Tough’s “The Inequality Machine”

The most obvious question to ask is why do so many of us care about so little of the population. What makes these schools different from all the others, worth $400k to parents who want nothing more than to brag about where their child got a diploma from? Much of this comes down to status and class. The university that you attend is a direct marker of status and certain universities are much better at bestowing status upon their students than others. Kennesaw State University has a different reputation than Stanford; we fall under a collective assumption that a student from the former is less qualified, intelligent, or creative than the latter. We rely on the system of admissions to operate as a probabilistic filter that selects for people with a high chance of future success, success that can come in many forms. Admitting a genius olympiad whiz kid gives you someone almost-provably smart. Admitting the son of a tech CEO with mediocre grades gives you someone with a capable network and cash to throw around. Admitting an athlete gives you a renowned program and hopefully a championship title.

The institutional interest of elite schools is to protect their brand, grow their endowment, and receive acclaim for any scholarship done on their campus. With that lens, it’s fairly obvious that universities operate to preserve their status by any means possible. Perpetuating an exclusive system for the top 0.5% of students helps a great deal.

Still, these priorities change over time and are often in conflict with the interests of others: professors, students, the government, etc. From an institutional standpoint, the system of admissions works very well. From the standpoint of a disgruntled rejected applicant, not so much. If, as a university, you want to champion diversity in academia, launching a counter-lawsuit against the government with opposed interests is very much in your playground.

There’s a few running themes that come up with elite universities making headlines. The false dichotomy between meritocracy and diversity, the issue of speech or politics on campus, and broad generalizations about admissions getting more difficult. There’s also the more subtle question of what do these elite university graduates actually do with their newly minted status.

On admissions generally, it is an imperfect, but effective system. A university has an interest in maintaining diversity in its class, racially, economically, major-wise, and more. That produces a better learning and social environment. Diversity is not always in competition with meritocracy, as conservative pundits might have you believe. ALDCs are probably next to blame—athletes, legacies, dean’s list, and children of faculty or staff. About 15% of Ivy League students are legacies and, more specifically, 43% of white students at Harvard can be bucketed as ALDC admits thanks to research by Duke Professor Peter Arcidiacono for the SFFA case (this is probably where the 40% number comes from,

). Some napkin math reveals that between 20% to 30% of students at elite universities aren’t there for their academics alone, though of course being a legacy correlates with a higher socioeconomic status which correlates with a greater chance at being accepted anyways.Despite these concerns, it would be hard pressed to find strong arguments relying on anything other than theory to say that this system is broken. For over a century, it is this very system that has produced top scientists, entrepreneurs, writers, creatives, and more. Apart from a desire for egalitarianism or an imagined equality, in practical terms, the admissions system is pretty damn successful.

And if you try to approach the system from egalitarianism, you run into several roadblocks that ultimately harm the institution, the student body, and the students themselves. Besides, who other than radical commies want egalitarianism anyways? Doing a score cutoff plus randomization ruins the demographics of a student body, and possibly eviscerates “unpopular” majors from academia entirely. Eliminating the personal statement or extracurriculars, the subjective part of admissions, doesn’t seem productive to creating a strong class. After all, you don’t want an entire class of 4.0 bots studying computer science! Writing and introspection (the two qualities that the essay really tests for) are important to have, if not just as a life skill. And still, all of these things are highly game-able by bright applicants who notice that or by rich families paying someone else to notice it for them.

You could propose a different system of application instead of the Common Application. It’s now far too common for applicants to “shotgun”, applying to dozens of universities hoping to land an acceptance at just one. Perhaps something like the UK’s system where you can only apply to five universities or taking notes from the residential match system could improve the state of things. For instance, you actually can’t apply to both Oxford and Cambridge, you have to choose one. Imagine if the Ivy Leagues agreed to do that as well?

We could bring back standardized test requirements, make them more difficult, or add in interviews with faculty. So, convince the school admissions to change something, CollegeBoard to change something, and pester tenured professors with wasting their time. No solution is easy or immediately optimal, but hopefully some combination of this all can be done.

Take out legacies and dean’s lists, keep in athletes and children of faculty or staff, limit the number of colleges one can apply to at 10, only two out of the Ivy Plus, test-mandatory, and throw in a departmental exam or faculty interview. If you were to ask me what I would change if I had the power to do it, I would probably do that.

Still, none of this answers the larger question about the purpose of the college. To get a job? A golden ticket to the middle class? To change the world? You probably don’t need to be told that most people at elite universities, about 60% in fact, end up “selling out” with some six-figure job. You also probably wouldn’t be surprised that these students vigorously defend their actions under some guise of effective altruism or inability to actually enact change, as this Harvard sophomore defends himself (then again, maybe a bit different when your high school costs $40,000 a year and has a shooting range). The practical purpose of an elite education has evolved into getting a prestigious job, as the numbers dictate. Learning is no more, university merely an instrumental good. What, then, to make of the average? The 99.5%, if you will.

The college wage premium, as the economists call it, still exists. The premium stands at about 70% as anyone with a bit of R and CPS data can show you. Lifetime earnings, while sources vary, are still significantly greater between a four-year degree and a high school diploma. In short, going to college improves your labor power on average. But, if you spend that time ChatGPT-ing everything, your human capital probably won’t see that much of an increase. Any flagship state school is equivalent in education to an Ivy League-level university, as my own experience has shown me. The primary difference is the people you end up surrounded by, and it helps in life to be surrounded by smart, rich, and high-status people.

There’s plenty of state-school graduates entering into high-paying fields, with tech likely being the most susceptible thanks to its larger hiring capacity. Not to mention, I’ve met a fair share of UIUC, Miami, and Bama grads at McKinsey and Jane Street. My point is twofold. While you shouldn’t treat college like a degree mill for a job, you have the option to. If you take that option, it’s possible to succeed no matter where you graduate from. That said, if you want to take the riskier path of using college to actually learn something or try and change the world, you absolutely should. So, go to college and make the best of it.

School, for Everyone

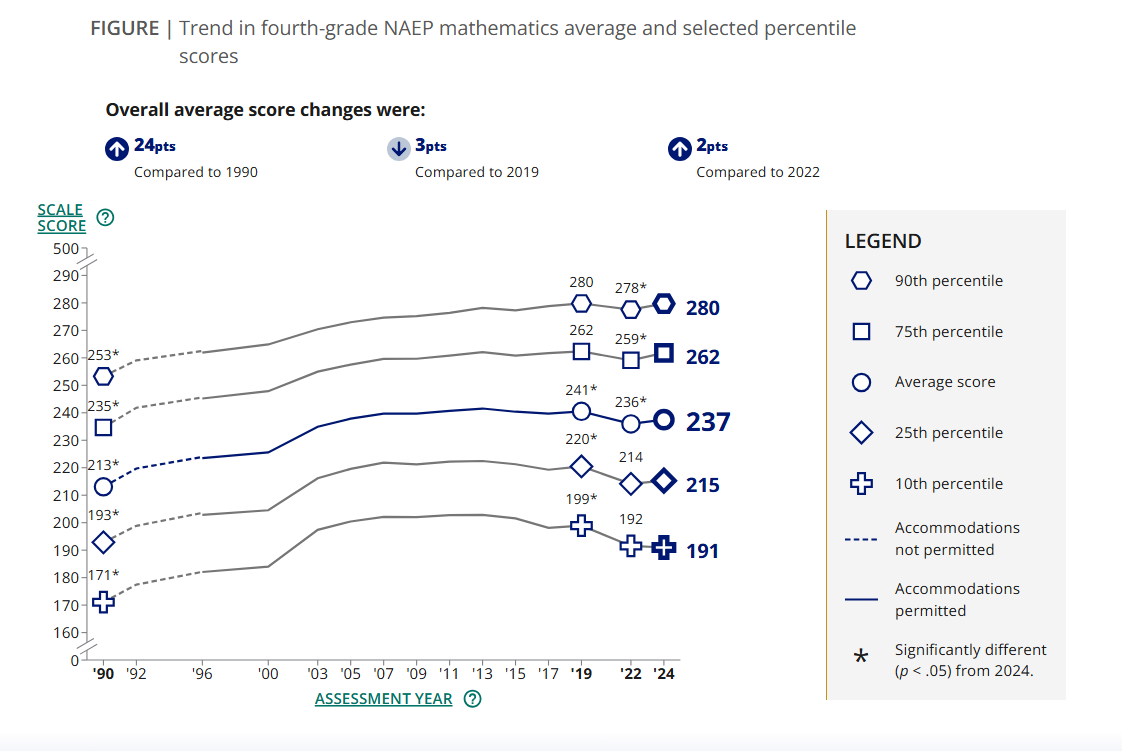

Enough of this essay has been about college (40% of high school graduates) and elite colleges (0.5% of high school graduates). But, there’s a lot more students than that. The pandemic seemed to drop school performance across the nation. In fact between 2019 and 2022, not a single state had improved in average student math proficiency in the fourth or eighth grade. An astonishing number of kids are failing at math proficiency. More than 70% of eighth graders failed the NAEP math proficiency exam last year. Maybe it’s common core or weird multiplication methods, but something has gone awry. Same for average reading proficiency, apart from children in military families educated in federal schools. Suffice to say, it’s pretty abysmal.

From 2022 to 2024, national averages for reading continued to trend down while math scores barely went up, still below 2019 levels. These scores have effectively been sent back by 20 years; two decades erased because of the pandemic’s effect on schooling. Note, that we’re not talking about cushy private schools or off-the-road charter schools, but all schools. While a few may be flourishing, most aren’t.

The last decade or so has seen a big push toward school choice and homeschooling, largely driven by conservatives fearful of public schools. In the same vein, they warn of ideological conversion at schools and hence cultural marxists, bathroom bills, and school board elections. The new thing is “patriotic” curriculums, history revisionism, and the displacement of hard subjects. The left pushes for public school lotteries, the removal of entrance exams, and against “de-laning”.

However, I don’t think that political rhetoric is the cause of stagnating test scores. Rather, a poor combination of policy and pedagogy has eroded both the capacity for public schools to teach and the ability for students to learn. The brain-rotted, ADHD-pilled, doomscrolling that many kids fall victim to isn’t helping either. Instead of pinning it on technology and attention spans (though it plays a part, don’t get me wrong), why not ask what schools are doing to mitigate these challenges?

The sad answer is that most of them aren’t. The share of kids who aren’t reading outside of school has steadily climbed. For that matter, so has the share of adults. A browse of the subreddit r/Teachers reveals that many high school English teachers are failing to assign full-length books. Like the elite college students from before, it seems like the lack of desire to learn starts from a painfully young age. Education, even when public and free, remains transactional.

Technology has some part to play. Educators are frequent in their complaints, with half of public school leaders placing the blame on cell phones. As more schools provide Chromebooks or tablets, educators fear that they’re only harming the performance of their students. Blame has gone from common core to phonics to technology in an endless game.

One way to get students to want to learn is to appeal to their curiosity and interests. It’s also clear that cell phones and laptops have little to no place in the classroom; they operate as obvious distractions. Kids need to start reading and they ought to be doing it earlier. I would bet money that if an elementary school dedicated a full hour every day for students to read a physical book along with a pop quiz, reading scores would go up. If kids aren’t reading outside of class, then make them read in class.

This individual teaching talk still misses a larger systemic point. If we want teachers to be well-equipped and prepared to teach a generation raised on technology, we need more of them and we need them to be treated better. Go back to that subreddit and you’ll find countless posts about burnout and turnover rates. If we’re going to overhaul school funding, gut administration and double the count of teachers. Raise their pay while you’re at it. Empower teacher’s unions to do more for their members.

Socially and on the family level, we need more people engaged in concerted cultivation. To make this easier, there needs to be more funding to make extracurricular activities accessible. Browse a search of all the national champions for this or that high school competition, and chances are, their house is worth well over a million dollars. If you want more people to be able to compete at that level, the materials necessary and travel expenses incurred must be subsidized. Expand school sports, make new after-school programs, and give free breakfast and lunch to everything. When every part of a student’s life is satisfied and distractions are set aside, their natural curiosity will let them learn.

And Onwards

Just because the kids aren’t okay now doesn’t mean that they won’t be. Change and adaptation is necessary at every level. But, this is the most important aspect to creating everything: productivity, capital, and unity. Education is meant to be a starting point. Its inequality is fundamentally questionable. If we want the most people to succeed, we need to start where they do. That means changing the first eighteen years of their lives.

If you feel differently about any of the points made, tell me why. I want to know your perspective, whether you’re in school, a teacher, or a parent. Trust, I won’t narc on your ChatGPT use.

Yeah as a high school student the amount of ChatGPTing is crazy. Like it can be the most basic assignment and people will ChatGPT it, and when it requires some busy work that doesn't really teach I understand, but like people just feed everything into it now. Everything we do is for the grade. It's like people forgot the point of school (at least in a sweaty Bay Area hs)